By Frank Layden, SI.com

BALTIMORE, Md. (May 18, 2014) — Many years ago a journeyman jockey watched a horse race on television. It was a Saturday afternoon in June 1973, approaching the end of the jockey’s career. By then he had crisscrossed the country so many times, and played so many hands of poker in so many jocks’ rooms at so many racetracks, that the memory of where he was that day has long disappeared into the mists of time. But the memory of what he saw has not. The jockey’s name was Art Sherman and the horse was Secretariat. On that late spring afternoon, Secretariat won the Belmont Stakes by 31 lengths in what is generally regarded as the greatest performance in horse racing history. It followed the colt’s victories in the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness, and completed racing’s Triple Crown for the first time in a quarter of a century, which seemed like a long drought at the time, but now not so much.

Sherman would ride a few more years, into his late 30s, and then he would become a trainer. He was successful, but not famous. Some of his horses were good, but none were great. He carried a memory of that June afternoon with him into middle age and far beyond, dreaming the horseman’s dream that one day a runner would come into his barn with wings on its feet and miracles in its lungs. A horse that made some people stand and scream, and others sit and weep. A horse that could pump life into a forgotten sport. One morning last week, Sherman, an impish 77 years old, leaned against a white-railed fence outside a horse barn at Pimlico Race Course. “That Secretariat, what a great horse he was,” he said. “I remember watching him run. All these years I’m thinking, I wonder if I’ll ever have a horse like that.” In the early morning light, Sherman shoved his hands a little deeper into the pockets of his green windbreaker, and looked over the top of his eyeglasses. “Well now,” he said, “maybe I do.” And then he smiled his little crooked smile, full of the impossible.

On Saturday evening, long spring shadows fell across Pimlico’s sandy oval as a chestnut colt named California Chrome rushed down the homestretch and past the ancient, crumbling grandstand, splashed with fresh red paint to ward off the ravages of time, and to hide the living metaphor of the racing game’s struggle. Jockey Victor Espinoza frantically waved a whip at Chrome with his right hand and thrashed at the reins with his left, keeping Ride On Curlin at bay. California Chrome flashed beneath the wire 1 ½ lengths in front to win the Preakness — his second victory in the last two weeks after his Kentucky Derby win on May 3.

LAYDEN: The victory of California Chrome and the magic of the Derby

It has been 36 long years since a horse last won the Triple Crown, when Affirmed outdueled Alydar in the Belmont, a drought so long that it has come to define its sport. So on June 7, California Chrome will run the Belmont Stakes, the 13th horse since Affirmed with a chance to close the Triple Crown deal. All the others have failed (and the most recent one, I’ll Have Another, in 2012, was scratched on the day before the race and didn’t even run). After his victory in Baltimore on Saturday, Chrome carried a question into the night, prodding a public wary by being burned too often.

Is this the one? The answer, for now is the same as always, hopeful yet cautious, excited yet defensive. A dream at arm’s length. Maybe. Just maybe. “That horse,” said trainer Bob Baffert, whose Bayern finished ninth in the Preakness, but who has three times taken horses to Belmont with a chance to win the Triple Crown, “is one serious horse. He is a stud.”

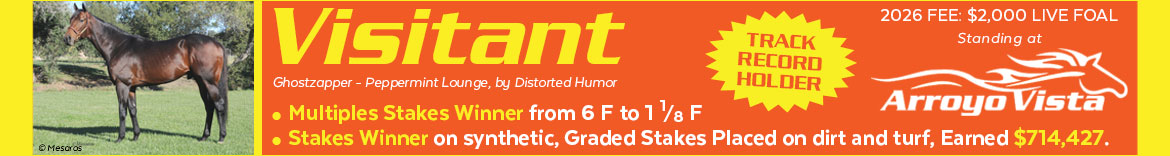

This much is true: A remarkable story is extended by three weeks and travels to New York to take a swing at history. It is the story of a sprawling family unlike any other in recent racing history. Not just the story of the septuagenarian Sherman, on the ride of his life, but also of his 45-year-old son and top assistant, Alan, a former jockey (who outgrew the silks at age 20), doing most of the daily work with Chrome. And also the story of the two men who turned a derisive backstretch rebuke into their stable name — Dumb-Ass Partners — and likewise turned the pairing of a slow-footed, modestly bred $8,000 mare and an unremarkable stallion with a $2,000 stud fee into a monster with four white feet.

One of the partners, Steve Coburn, a 61-year-old press operator at a Nevada factory that makes magnetic strips for credit cards and hotel room keys, is never at loss for words. Before the Preakness on Saturday he found Sherman at the barn, and when Sherman asked if he was nervous, said, “I’ve only crapped my pants one time.” (Sherman, knowing his owner, quipped, “He was 1-to-5 odds to say that.”) After the race Coburn, whose personality grows daily, said, “We just hope that this horse is letting America know that the little guy can win. I honestly believe this is America’s horse.” He is the story’s purposefully cornpone narrator (but one who also launched a withering criticism of the hospitality of Churchill Downs at the Derby).

The other owner, 58-year-old Perry Martin, owns a testing lab outside Sacramento. He was so unnerved by the crush of media attention at the Kentucky Derby that he didn’t attend the Preakness and was sending cell phone calls directly to voice mail well into the evening on Saturday. The story of Coburn and Martin is reminiscent of the story of 2003 Derby and Preakness winner Funny Cide, owned in part by six high school friends from upstate New York who traveled to Triple Crown races in a yellow school bus because they couldn’t afford a nicer vehicle. But Funny Cide, a New York-bred gelding, was purchased for $75,000, veritable sheikh’s riches compared to the cost of California Chrome.

LAYDEN: California Chrome: The Accidental Favorite

The colt has now won six consecutive races, beginning with a modest stakes event in California on Dec. 22. (“He’s won five in a row, so that starts to feel a little spooky,” said Sherman before the race, with an old hand’s bow to silly superstition. “Can he win six?”) Yet entering the Preakness, cynics picked at California Chrome’s record. They suggested that his Derby had been slow (which it had). They argued that he had benefited from a series of perfect tactical trips, with nary a straw in his path, to use the hoary parlance of the game (this was also true, but owing in large part to the horse’s transcendent athleticism and the superb horsemanship of Espinoza, who began riding Chrome at the start of the winning streak). His Preakness victory was an emphatic response to all of this, a performance that was both fast and tough.

It did not surprise his handlers. Four hours before the race Alan Sherman stood in the shedrow of the Pimlico Stakes barn, no more than 20 feet from California Chrome’s stall. A bale of hay was hung outside the colt’s door. Then it was replaced with a green tether ball. Sherman looked over his shoulder as Chrome stood as still a statue. “Look at him,” said Sherman. “Totally in chill mode.”

At a few minutes before six, California Chrome made the walk from the barn area to the infield saddling area. But unlike the Derby, when Chrome was aggressive and sweating in the paddock, he was as cool as a pony giving rides at a birthday party. “Handles everything,” said Baffert. “I watched him in the paddock today. Nothing was bothering that horse.” Next to Chrome, the lightly raced and high-strung Social Inclusion dragged his groom along the grass. Chrome seemed not to notice.

Social Inclusion’s antics would not be the only surprise of the day. First Espinoza had to get California Chrome to break cleanly, which is always an issue because Chrome’s one foible is that he rolls his head from side-to-side in the starting gate, leaving him susceptible to slow starts. In the Derby, Espinoza encouraged Chrome from the gate; Saturday in the Preakness he did it again and got a solid start from the No. 3 post position. Then Espinoza drifted intentionally to the outside to create a longer path to the front for expected pacesetters Social Inclusion and Bayern. That is when everything changed. Most handicappers had expected that Social Inclusion and Bayern would shoot to the front of the field and cook through fast early fractions. They did not. Instead, Pablo Del Monte from the No. 9 spot gunned to the front. And then, stunningly, overmatched filly Ria Antonia also shot past Chrome as they passed underneath the wire for the fist time, forcing Espinoza to make rapid-fire decisions.

“The one horse went by me,” Espinoza said of Pablo Del Monte, “and then there’s another horse that goes by. Wow, this is crazy.” Espinoza tucked in behind Pablo Del Monte and Ria Antonia and drifted outside through the first turn, creating a clear path down the backstretch.

“You get a plan in your head as to how the race will be run,” said Hall of Fame jockey Jerry Bailey, who had analyzed the race for NBC’s telecast. “And then all of a sudden it’s completely upside-down. That’s very difficult. You might say, Well, there’s still two horses in front, even though it’s not the two Victor expected. But Victor has to wonder, When are the speed horses coming?”

He didn’t have to wonder for long. With more than half a mile remaining in the race, Social Inclusion and jockey Luis Contreras raced up to Chrome’s flank. The challenge came much sooner than Espinoza would have liked. “I had, like, a tenth of a second to decide what to do,” said Espinoza. “So I decided to go. California Chrome quickly finished off Ria Antonia (who would finish last) and Pablo Del Monte. Social Inclusion hung alongside for nearly a quarter mile and then, he too was cooked. “Right then,” said Bailey, “Victor had to be thinking, OK, I can give him a little breather. But then here comes [Ride On Curlin].”

In the seats, Espinoza’s older brother, Jose, who continues to recover from a brain injury suffered in a spill at Saratoga last Aug. 17, watched Victor fight off repeated challenges. “They kept attacking him, all these horses,” said Jose after the race. “It was really tough.” Victor, whose cool demeanor meshes perfectly with Chrome’s, would call the tactical scenario “complicated.” He never did give Chrome that breather, but instead rode him furiously through the lane. Ride On Curlin, one of only two Derby finishers to wheel back against Chrome in the Preakness, closed furiously from the outside, but never ran him down. (Ride On Curlin’s trainer, (Bronco) Billy Gowan, said he’ll go to New York, as well. “Heck yeah, I want to try him again,” Gowan said. “My horse doesn’t want to stop runnin.”)

LAYDEN: Victor and Jose Espinoza share a career but lead two different lives

Past the wire, Espinoza raised his whip in the air. Chrome’s winning time of 1:54.84 was the fastest since Big Brown’s 1:54.80 in 2008. It was 12 years ago that Espinoza won the Derby and the Preakness for Baffert on an ornery speedball named War Emblem. Espinoza was 29 at the time, but new to the biggest stage in the sport. He squirmed in the spotlight and didn’t enjoy the run. “I tried to do too much,” he said. On the day of the Belmont, War Emblem stumbled from the gate and was beaten before he had taken three steps. The pressure and the failure have dogged Espinoza since that day.

Now there is another chance, a reach at history for horse and rider. And for all of them, a race to slake the sport’s thirst. Just maybe.